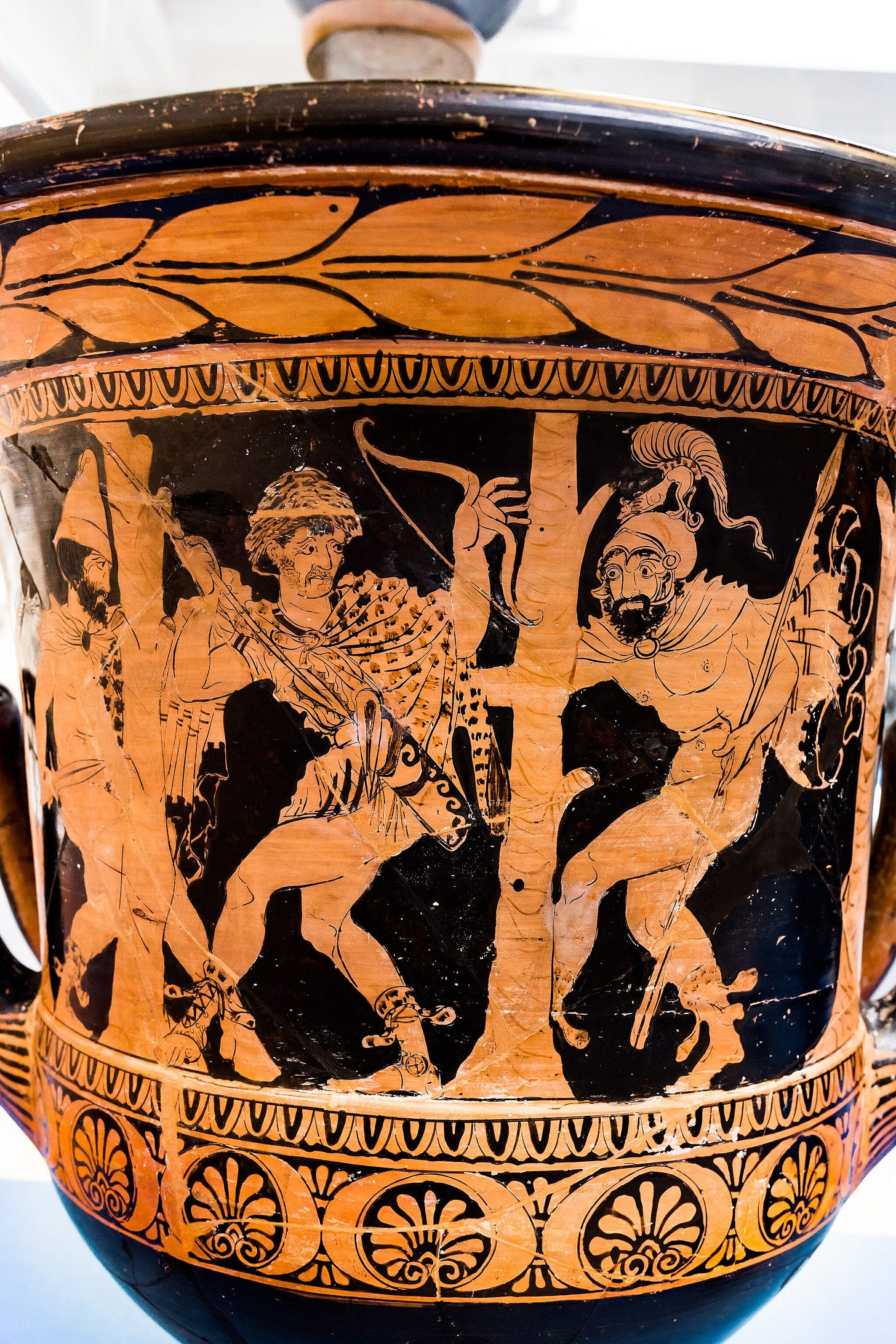

In Book 10, Dolon, from the Trojan side, takes up Hector’s challenge to spy on the Greeks in return for the promise of Achilles’ horses. Meanwhile, Agamemnon is rousing his own men to spy on the Trojans. Diomedes volunteers, and picks one of the other volunteers, Odysseus, to come with him.

I’m kinda chuffed that I remembered that Dolon was mentioned in the Aeneid, too, in Book 12. He was the famous father of a son who would be killed by Turnus.1

Here’s the expanded story, in the Iliad, which makes him look much less heroic to me.

Diomedes and Odysseus have already gone past the ditch that separates the Greeks, camped by their ships, from the Trojans, when they hear Dolon coming towards them. Dolon also hears them, but since he believes himself still to be in Trojan territory, he assumes they are allies until it is too late. When the Greeks capture him, he begs to be held for ransom, and Odysseus lets him believe his life will be spared and he will be ransomed. It’s just a ruse, to get information out of him.

From my point of view, then, he tells the enemy everything they need to know, and points out Rhesos as a good target for the Greeks to attack, since his men have just arrived and haven’t set a guard. I was taken aback by that, because he actually offered information that the Greeks hadn’t specifically asked for. But it does not seem to me that his spilling all this info is considered a cowardly or dishonorable thing at all, at least so far, in the Iliad. Nor does Virgil portray Dolon that way in Book 12 of the Aeneid.

What am I missing? How can it be consistent with honor to point your enemy to a good target, without even trying to hold back the information?

I showed my first century Romans this description of Dolon from the Iliad:

ἦν δέ τις ἐν Τρώεσσι Δόλων Εὐμήδεος υἱὸς κήρυκος θείοιο πολύχρυσος πολύχαλκος, ὃς δή τοι εἶδος μὲν ἔην κακός, ἀλλὰ ποδώκης: αὐτὰρ ὃ μοῦνος ἔην μετὰ πέντε κασιγνήτῃσιν. Iliad, book 10, lines 314-317

but there was among the Trojans a certain man named Dolon, son of Eumedes, the famous herald- a man rich in gold and bronze. He was ill-favoured, but a good runner, and was an only son among five sisters. — Translated by Samuel Butler

“Okay, so ill-favored –”

“Still, he’s a fast runner. And rich. Son of a great herald. Rich means favored by some god or other. At least his father was. Only son, though, with five sisters, that would be expensive ….”

“No kidding. A decent dowry for five girls? Yes, Daddy’s rich, but then again, it means he’s not looking for just anyone to marry them off to.”

“Not just that. Remember what happened to Andromache? When brothers die, their sisters become captive wives. Or worse.”

“So sad. No one to avenge his death. Or to handle the funeral rites. Or to serve the household gods….”

In Latin and English translation from the Aeneid:

Parte alia media Eumedes in proelia fertur, antiqui proles bello praeclara Dolonis, nomine avum referens, animo manibusque parentem, qui quondam, castra ut Danaum speculator adiret, ausus Pelidae pretium sibi poscere currus; illum Tydides alio pro talibus ausis adfecit pretio, nec equis adspirat Achillis. Aeneid book 12, lines 346-352 Elsewhere on the field Eumedes charged Into the melee – a man famed in war, Son of the fabled Dolon – having his name From his old grandfather, his recklessness And deft hand from his father, who had dared To ask Achilles’ team as his reward For spying on the Danaan camp at Troy. For that audacity Diomedes gave A different reward: all hope expired For horses of Achilles. Robert Fitzgerald, translation lines 474 - 483

The problems of alliances were front and center in the Iliad. Dolon had put his tribe/clan first as many would've expected of the time.

"Of course, you protect your family over some clan that 'claims' to be allies with the Trojans. We don't trust them. We never have. They'll turn on Troy, and us, the first chance they get."

The Greeks had their own tribal clashes that mirrored the clash of their 'kings.' All of those men fighting for status in the alliance, daring great deeds and bringing back treasure to showcase their status as warriors and leaders.

I took some time to ruminate on the question you posed to The Brothers Krynn and I after first reading it through yesterday. Then, before adding it to this weeks Sword & Saturday list, I read it again and gave your question further thought.

Dolon's position provides some interesting considerations. On the one hand, it's very easy to say that freely giving the information about that Trojan position is downright traitorous to them, and thus he shouldn't be considered a hero at all. Leaving it at that would be very simple and I'm sure many would be satisfied to do so. However, you mentioning that neither the Iliad nor the Aeneid seem to portray him as dishonorable has me thinking about other possibilities.

Firstly, given that these are Greek poems, it's possible that there's a little home team bias at play here. Dolon's actions ultimately would've served Agamemnon. Ergo, it served the Greek position in this conflict, which could result in him being painted as honorable. Personally, I think this is also a bit too simplistic. While it's been a very long time since I read excerpts from these works - this thought piece is a great reminder for me to add them to my eternally growing list of "stuff I need to (re)read" - part of me can't help but wonder, based on what you've shown us here, if both Homer and Vergil approached Dolon with intentional neutrality.

I fully admit this could just be me projecting my personal biases onto this, or that I'm overthinking the situation, but it strikes me as interesting that the way Dolon is described simultaneously paints him as explicitly ill-favored and stuck in the unenviable position of being the only son in a family stuffed full of daughters, while also showcasing his achievements and the decent status of the family he comes from. To me, this decision to highlight the shortcomings of Dolon and his lineage, while also lauding their accomplishments, comes off as an intentional effort to paint him in a very neutral light. Which is to say, it's almost as if Homer and Vergil are begging the same questions of Dolon that you do, here.

Again, I could be making wild assumptions here, it's been a long while since I've read any Greek literature. Still, I found this line of thinking interesting, so I figured I may as well follow it to what conclusions I could find.